The eponymous nine-year-old schoolgirl from 1994's Umihara Kawase (key art above) is a sushi chef, her name supposedly* derived from the Japanese adage, "sea fish are fat in the belly, river fish are fat in the back." She navigates her dreams—which are dotted with the occasional bipedal fish or human-sized vegetable, as dreams often are—with the help of an elastic fishing line. A sequel, Umihara Kawase Shun, was released in 1997, increasing the challenge from strenuous to downright Foddian.

To recap: these are games with a national dish for a visual motif, a colloquialism for a title, and an 85° angle for a difficulty curve. It shouldn't take an MBA (does anything?) to realize that localizing and marketing a threequel to a Western audience—16 years(!) after the previous installment, mind you—is a fool's errand.

...

Sayonara Umihara Kawase is a threequel localized and marketed to a Western audience as Yumi's Odd Odyssey 16 years(!) after the release of its predecessor, foolishness be damned. And the ace up the marketing team's sleeve? I'll let you try to spot it.

Chiropractic medicine must be a pretty lucrative gig in Japan.

Er, them.

It's perfectly understandable, if a little juvenile, that the business suits went down this path. What else could they have done? It's not like the Steam Page was doing much of the heavy lifting:

"The elasticity of Umihara's fishing line sets the Umihara Kawase Trilogy apart from other games, giving unprecedented levels of mobility and discovery. Tightening the line or giving lots of slack can be the difference between success or failure. The elastic nature of the fishing line allows the player to stretch down to otherwise unreachable areas or be catapulted upwards."

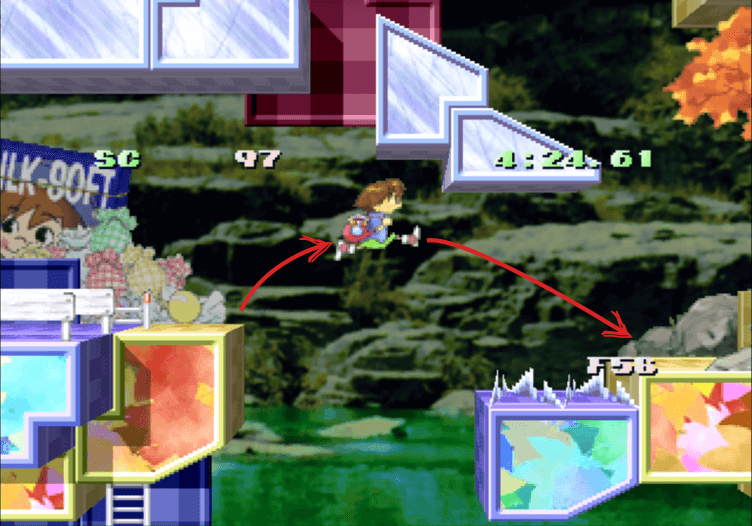

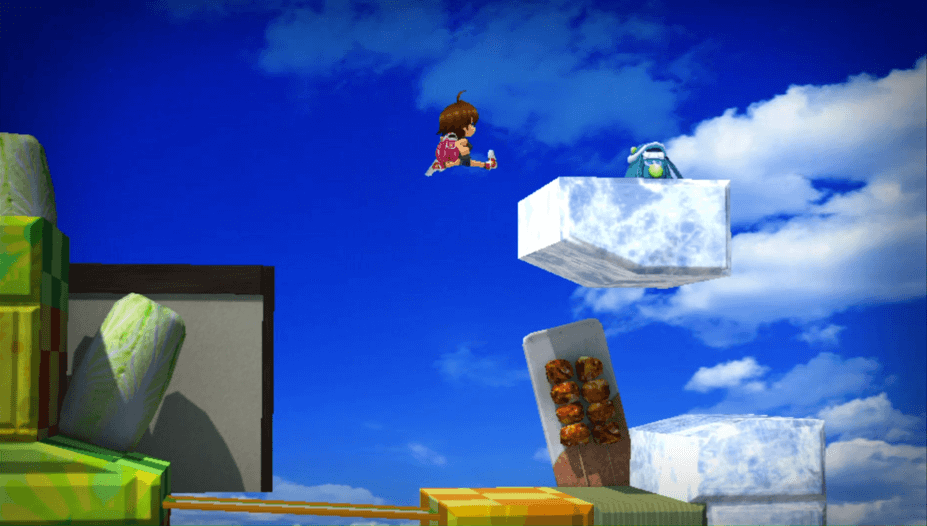

Some gameplay from Sayonara.

A far cry from the promo art, as you can see.

That blurb, dry as it is, belies the fishing line's nuance—it wraps around corners, inherits from and transfers momentum between jumps, and even conceals beneath its surface a handful of advanced techniques.

Umihara Kawase Shun, being both a sequel and altogether hostile towards the player, plumbs the depths of these techniques and demands them (they were largely optional in the 1994 original). Most notable among them is the rocket jump, which allows for rapid horizontal movement and jumps across wide chasms, as seen below.

Please enjoy my arrows. (Calling them vectors would imply

a knowledge of physics that I sorely lack.)

Sayonara, in contrast, dumbs down and largely tables the rocket jump, sanding down the series' texture in hopes of lowering the barrier to entry. There are other design concessions, too: the momentum gained from reeling in your line has been dramatically increased, trivializing vertical levels, and a time-stop mechanic has been shoehorned in for bailouts. If the first two titles were an inch wide and a mile deep, then Sayonara has retained the width, but lost some depth; it's not giving players more, just asking less of them.

The news isn't all bad, though, thanks to a streamlined progression system: there are no lives outside of the game's "Survival Challenge," which preserves the series' arcadey, run-based structure while encouraging practice and experimentation. Backpacks, a collectible present in every game, must now be brought to the end of the level for their collection to count (in past games you could nab them, die, and still see them show up on your save file). And perhaps best of all, the enemy placement is less Ninja Gaiden (NES) and more Ninja Gaiden: Ragebound, if you catch my drift.

Collecting backpacks was an afterthought in the previous games,

but is brought to the fore in Sayonara.

I've had to peel myself away from the controller many a time this past month. The elastic fishing line of Steam Page renown really is that impressive—just thinking about the math involved makes my head hurt. There's something truly alien about these games, not just in their cultural specificities but in their control schemes. It's refreshing, albeit tough to recommend for a casual playthrough (even the watered-down Sayonara).

How do you sell a niche game to a new market? Trust that men boys will be boys everywhere, I guess.

*This is one of those times where everyone points to Wikipedia even though their sourcing is shoddy, to say the least.