"I consider that a man's brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose... It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent... It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones."

- Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet

I love this analogy, and the introspection that it prompted in thirteen-year-old me cannot be overstated. What was filling up my attic? What had the conveniences of the 21st century cleared out, and what had the clamor of the internet crammed in?

These questions still resurface, on occasion, their answers ever in flux as practical knowledge inevitably loses ground to memes and media. Why must I check the back of the pasta box for cooking instructions EVERY SINGLE TIME? Why do I represent 20% of the viewership on a "How to Tie a Tie" video? And why, then, with these glaring gaps in knowledge, did I remember Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy so thoroughly?

I didn't even beat the game, only playing for a brief stint in March of 2024 before throwing in the towel. No ill will, no broken mouse—just a waning interest and a resolve to come back later.

For the unaware (¡hola, hermana!), Getting Over It is commonly referred to as "ragebait." Purposefully opaque and proudly obtuse, ragebait not only challenges the player, but heckles them while doing so.

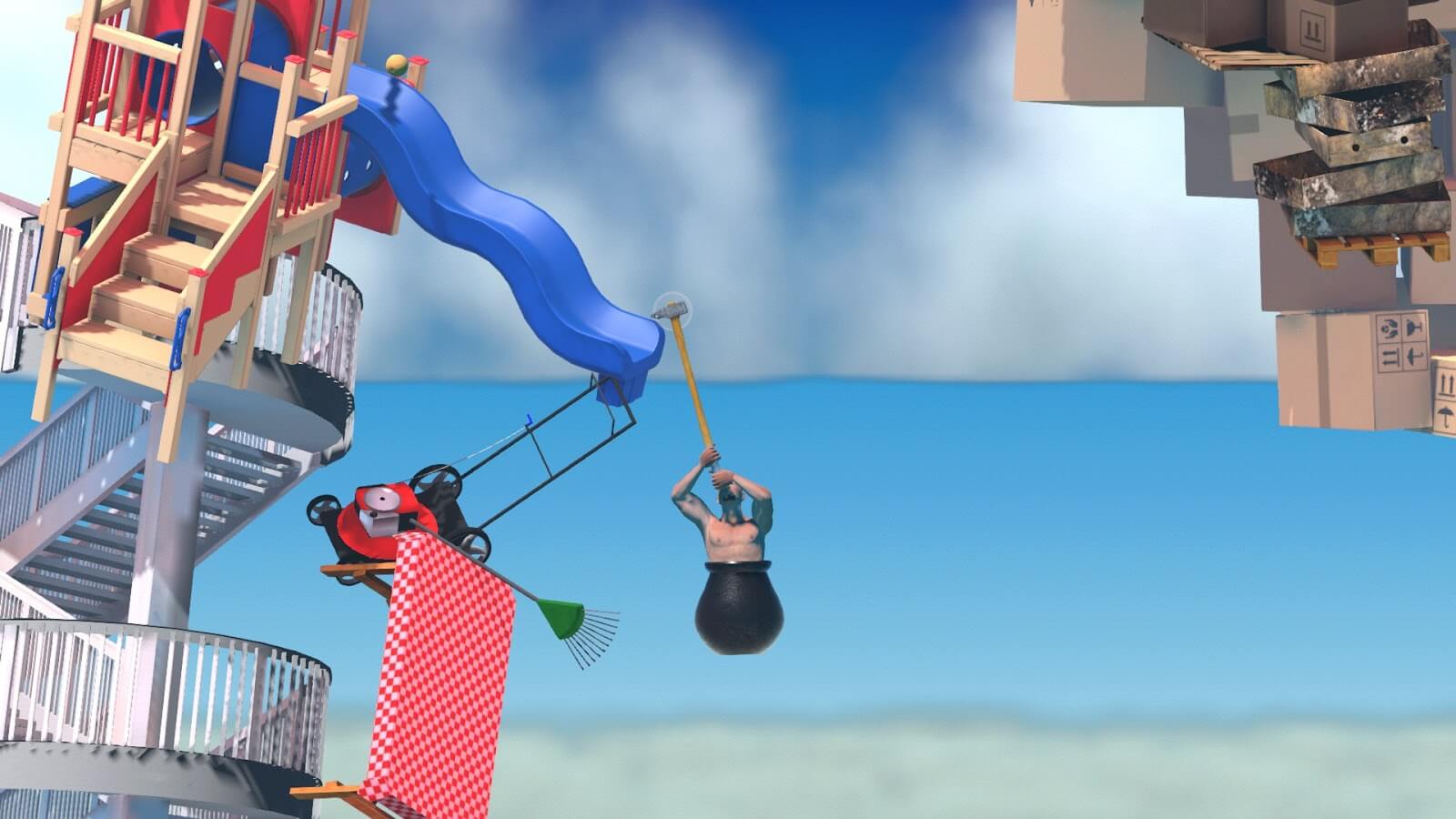

In the case of Getting Over It you play as Diogenes, armed with your trusty hammer. You wave your mouse around, and Diogenes waves back, hammer in hand.

Hello, Diogenes!

You must climb the mountain. The narrator, Bennett Foddy, tauntingly instructs you to do so. He thinks you can't. So you climb. You climb to rub your eventual triumph in Bennett Foddy's smug, stupid face.

But then you discover that climbing is hard?!?

In all seriousness, Getting Over It is tough. Muscle memory, stiff from years of homogenous control schemes, knows not what to do with the hammer that is your mouse. So you flail and you fumble your way past the initial obstacles as Foddy waxes eloquent about the softness of the modern gamer. It stings.

I flailed and fumbled for about three hours, stopping just shy of halfway to the summit. I think I was grinning the whole time. Grinning at my stupid monkey brain for spending three hours of limited existence on something designed to chafe and abrade.

And now I sit grinning at my stupid monkey brain once again, this time for preserving in the attic that is itself a tiny space for Bennett Foddy and his incensingly beautiful game. After more than 18 months, I retained the three hours of "skill" (I use the term loosely) I developed with Getting Over It. The once hours-long section was now behind me in a matter of minutes.

I remembered the control scheme. I remembered the obstacles and their sequence. Even Foddy's narration was dusted off in my brain-attic. Such clutter to have persisted those long 18 months!

This, dubbed "orange hell," is as far as I progressed my first time around.

Getting Over It has a lot to say about clutter, about trash. The game itself is an homage to 2002's Sexy Hiking, a B-game of middling renown. In Sexy Hiking you likewise climb a mountain with a hammer. Foddy relates that he was enamored by this piece of trash (his words), that yet another piece of cultural clutter had a spot reserved in his brain-attic (my words).

He later narrates:

Everything's fresh for about six seconds

until some newer thing beckons

and we hit refresh.

And there's years of persevering

Disappearing into the pile

Out of style

Out of sight.

Per Foddy, everything is not (necessarily) trash because of its quality, but because it is consumed and discarded so fleetingly. That's a convicting sentiment in a you-are-what-you-buy society, and moreover one that Getting Over It combats simply by existing—Foddy took a dismissible game, Sexy Hiking, and gave it the time and attention he thought appropriate. His homage kept and continues to keep it from "disappearing into the pile."

This commentary on trash is appropriately shared

as you traverse a landfill of level geometry.

I am not Sherlock Holmes. Instead of the ideal cooking time for al dente noodles or the proper steps for an immaculate Windsor knot, my brain-attic is, in and of itself, a receptacle for a fraction of the digital culture's overall trash. But while everything may start as trash, it doesn't have to stay that way.

To me, one of Getting Over Its most prominent messages is that marinating in and sitting with trash is what gives it value—that we ought to slow down, wait to hit refresh, and really, truly contemplate that which we somehow lapped up from the fire hydrant of culture. That we ought to keep a game, a book, or whatever tucked away in our brain-attics for months, years, and chip away at it, reflect on it, or come back to it later. Only then can the clutter in our brain-attics transcend from, as Sherlock says, "useless" to "useful." From cultural trash to personal treasure. From Sexy Hiking to Getting Over It.